The Problem With New Year’s Resolutions

January 21, 2023

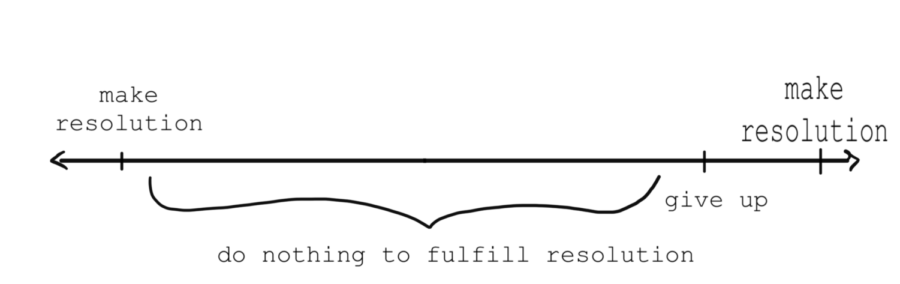

I didn’t write any resolutions for this year. I used to try to come up with goals for the year or things to check off of my bucket list, but in the past few years I’ve stopped. Whatever their reasons, a lot of other people are making the same decisions—according to a CBS poll, about 29% of Americans made New Year’s resolutions in 2023, down from 40% in previous years.

Why is that? What caused our 25% decrease in self-improvement fanaticism? Well, when you make a goal, you generally do it with the expectation that you’ll achieve it. The problem with this is that New Year’s resolutions aren’t goals—they’re wishes. Generalized New Year’s resolutions such as “get in shape” or “write a book” are foggy definitions at best. If you want to get something done, you need both a finish line and a plan to get there. Making a proper resolution requires effort!

Another cause for this decrease in resolutionizing (resolving? resoluting?) is a certain degree of exhaustion with the phenomenon. Maybe we’re tired of being told that we need to be better. Maybe people have realized that failed New Year’s resolutions are half of the reason that gyms can afford to stay in business. Or maybe folks are trying something different and practicing more self-acceptance. New Year’s resolutions are sort of a cultural thing—the saying “new year, new me” didn’t appear in a vacuum—but culture changes.

Despite my tone, I don’t hate New Year’s resolutions. I think it’s a laudable goal to try new things, to aim for growth and improvement. But I don’t like doing it with a looming cloud of undefined ambitions hanging over my head.