Recently, I read the book Interstellar Megachef by Lavanya Lakshminarayan after picking it up in my local library. I was drawn in by the wacky title, and after reading the synopsis, I checked it out under the impression that it was about a sci-fi cooking competition with a side of speculation on the implications of simulated reality technology.

It is not that. I shan’t spoil too much, but it is really not that. The cooking competition isn’t the narrative focal point I’d hoped it would be, and, equally unfortunately, speculation on the wider effects of simulated reality technology isn’t really dug into until the last seventy or so pages—I am very excited for what they’ll be exploring in the sequel, however. Lakshminarayan has laid the groundwork for a truly gripping examination of human escapism and detachment from reality, as well as the level to which propaganda and advertisements will be able to infiltrate our minds as technology advances. Additionally, she explores themes of imperialism and the pressure of assimilation in a way that, while at times is heavy-handed, is undeniably effective and accurate to the realities of many. Despite its cheerful cover, Interstellar Megachef is far from the “Great British Bake Off But In Space And With Lesbians” that it is inexplicably billing itself as. I would hesitate to call it gritty, but wouldn’t argue if someone else did.

Which leaves me with a question that I seem to be asking myself far too often these days: why the heck is this book trying so hard to market itself as something it is so clearly not? The cooking competition is a plot device, not the plot itself, so why center the marketing around it? Why not focus on the actual meat of the story, an interrogation of the rhetoric behind assimilation and how we perceive culture? Interstellar Megachef is saying something that is very important in a highly unique—and entertaining—way, so why on Earth would it not focus on that?

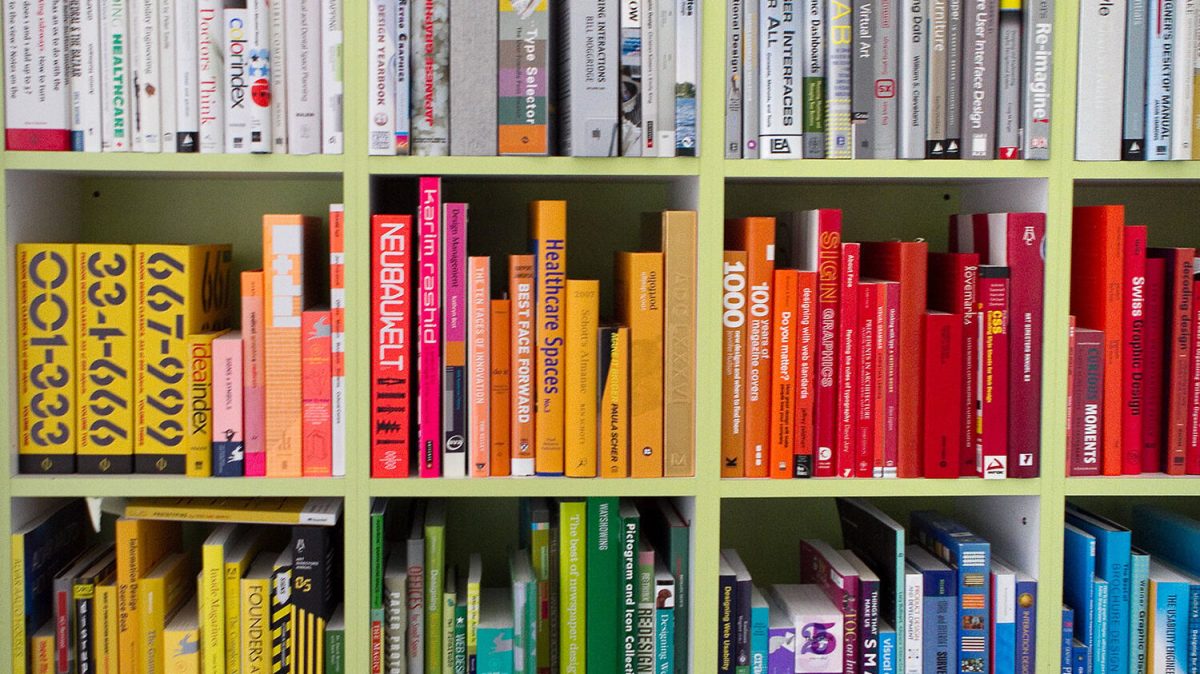

Despite pithy platitudes, readers do judge books by their covers—that’s kind of the point of them. And when those covers and synopsi are deliberately misleading readers, they end up alienating those intrigued by presented concepts when the promised Lesbian Bake Off turns out to be mostly about imperialism. Not only that, they also end up missing all the prospective readers who would enjoy reading what Interstellar Megachef actually is, but don’t pick it up because it’s being outwardly presented as something completely different. In fact, the only readers this marketing strategy “works” on are those who would enjoy both the lie that is sold to them and the thing that the book actually is—a much narrower audience than just…selling the book to people as what it is! Lying about this is stupid and convoluted!

And yet it is disgustingly common. Not all examples are as stark as Interstellar Megachef, but if you’ve looked at any given debut novel published in the last couple years, you’ve likely read a tagline written to the tune of “X Well-Known Piece of Media meets Y Well-Known Piece of Media!”

One example of this is Iron Widow, Xiran Jay Zhao’s debut novel, which carries the tagline “Pacific Rim meets The Handmaid’s Tale”. This, by some metrics, is accurate. The story features big robots punching monsters, and also there’s a sort-of plot relevant wall that keeps the monsters out of some places. It also features a female protagonist who rebels against a heavily misogynistic system. But the similarities largely end there, because Iron Widow is a unique novel that is a whole lot more than the cookie cutter tagline it got slapped with thanks to a practice in publishing called comp titles—short for comparable titles.

Most books—especially debut novels or ones from relatively unknown authors—are required, or at the very least heavily suggested, to come up with several pre-existing popular titles that their book is comparable to in content, genre, tone, etc. It’s not just used when marketing the book to the audience, however—they’re also integral to convincing many publishers to take on an unproven manuscript. Zhao has spoken online at length about their struggles with publishing for these very reasons, as many publishers simply felt that their novel wouldn’t sell, as it deviated too far from established successes.

Large publishers don’t want to take risks, they want guarantees. The easiest way to get that is to sell something as close as possible to preexisting hits—something that very few people actually want to write, thus creating an awkward situation wherein authors have to convince publishers their book is something it’s not, so the publishers will pick it up and proceed to sell it to readers as something it’s not. Comps are a self-enforcing trend at this point, practically an industry standard. It’s a big, yucky feedback loop that won’t end until publishers realize that these tactics, when taken too far, can end up alienating potential readers.

The unfortunate truth is that they’re probably never going to realize that, because for all intents and purposes, comps…mostly work? It’s the clickbait of the literary world, sure, but clickbait is popular for a reason. If you don’t think about the wider implications of comps, like many authors have to, there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with them. Sure, sometimes they misrepresent a book a bit, but most of the time they work fine as a snappy little hook to draw readers in. Pacific Rim meets The Handmaid’s Tale does sound really, really cool, even if it fails to capture certain aspects of the narrative.

I can’t bring myself to claim that comps are inherently bad. They’re a symptom of an increasingly insular publishing industry, sure, but I think they can legitimately help authors gain a larger audience.

But as always, the poison’s in the dose, and the publishing industry is laying it on thick. All too often, it seems like publishers are trying to cram these unique, diverse stories into boxes that simply don’t fit. You can only stretch a comp so far until you’re flat out lying to readers, which, as I’ve discussed, rarely ends well.

As judging a book by its cover becomes increasingly difficult, readers beware. But most importantly, readers, keep an open mind, and embrace books that are a little out there. Neither comps nor their influence on the publishing industry are going away, so all we can really do is make an effort celebrate the books that they screw over the most.