Killers of the Flower Moon, an adaptation by acclaimed director Martin Scorsese of the nonfiction book of the same name, is many things. For one, it recounts the story of how the Osage nation, the richest people per capita in the country in the early 1920s after discovering oil on reservation land, were systematically exploited and serially murdered by white settlers for their wealth. On a smaller scale, it recounts the stories and marriage of Mollie Kyle and Ernest Burkhart, an Osage woman and inheritor of a massive oil estate, and a white war vet who married her after returning to Oklahoma to live with his cattle magnate uncle William “King” Hale. It also tells the story of the early days of the FBI, as well as a smattering of other little stories scattered across its expansive runtime. The experience of watching the film is akin to sitting through three of the densest APUSH lectures you could have without a single breath for notes, with information often being thrown at you in one scene only to finally be paid off 2 hours later. It’s quite a lot, and it’s generally an exhausting movie experience to behold. Thankfully, it’s also easily the most engrossing, heartbreaking, beautiful, and important film to come out this year.

The story Killers tells upon its wide narrative canvas is not an easy one to digest, and the film never shies away from that fact, content to portray every aspect of its story in all its gutting detail. The film is methodical in its presentation of the systemic racism enacted against the Osage nation, from the incompetence program by which Mollie Kyle (played excellently by Lily Gladstone— more on her later) is introduced where Osage people like Kyle were labeled “too incompetent” to handle their massive wealth and were forced to report every spending to white handlers, to the way white men such as William King Hale (Robert De Niro) and his nephew Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio) integrated themselves into Osage communities as a way of siphoning off and inheriting their wealth for themselves, to the matter-of-fact way the same men blatantly murder members of that same community without so much as an investigation from police. The film depicts acts that are monstrous and terrifying and heart-wrenching, and lists them as if they’re just another moment in a life– which, for the monsters who enact them, they often were. It’s overwhelming at times, which, compounded with the mundanely sickening way Scorsese shoots the moments of outright violence, often makes the film a necessarily miserable experience.

What saves the film from being a pure exercise in misery is the undeniable craft and empathy with which it is made. Scorsese’s efforts towards bringing this story to life authentically are clearly painstaking, and they pay off in spades throughout the runtime. The film, shot by multi-time collaborator (and Barbie cinematographer) Rodrigo Prieto, is easily one of the most beautiful of the year, filmed with expert command of light and blocking and with some of the most gorgeous natural vistas you’ll ever see, all helped by some incredible and on point production design, costuming, and location scouting. More than just a pleasing exterior, the filmmaking enhances some of the best scenes of the film, lending a spiritual and elemental significance to everything it touches (a scene of an Osage matriarch’s death and a scene of a married couple arguing against windows of dancing fire come to mind). What’s more impressive than the aesthetic prowess of it though is the pure compassion Scorsese shows in the story. He spends the first half developing the love story between Ernest and Mollie, which is genuinely touching and complex at the beginning even as you’re aware of the inevitable end. Where the film could’ve simply been a true crime procedural about white cops investigating the serial murders of indigenous people, the film’s centering on the marriage between Mollie and Ernest lends it a much more personal and powerful lens on the systematic devastation against the Osage people. Both characters get hefty amounts of attention paid to their perspectives. Ernest is effectively developed as an idiot lackey of his uncle’s who it seems does genuinely love Mollie, and is unable to reconcile that his actions out of his love for money and loyalty to White America have irrevocably been at the detriment of her. Mollie, meanwhile, is portrayed with an acute awareness of the destructive impacts that white settlers have had on her people, enduring and fierce to no end while also allowed an equal amount of vulnerability; a moment when she crumples over and lets out a mournful screech for the first time is one of the most affecting in the film. Yet her perspective is painted in grays; she also clearly loves Ernest, and is in denial of his complicity in her sisters’ death. Despite this being the meeting of the two primary stars of Scorsese’s career (who are both very good, De Niro as essentially the devil doing a Trump impression, and DiCaprio doing a Grumpy Cat impression), Gladstone as Mollie acts circles around everyone here, conveying so much intelligence, warmth, quiet intuitiveness and sorrow in a few short looks. As any Scorsese women protagonist, she inevitably, unfortunately gets the shaft here, relegated to the sickly, helpless wife role for most of the middle third, but there’s an awareness of that, an indictment of the men who poison and gaslight her and her people into a quiet death— and she eventually gets to come back in the end for emotional retribution in one of the best scenes in the film. The film’s ultimate flaw is that she’s not more of the main focus.

Scorsese’s other films such as Goodfellas, The Departed, and The Wolf of Wall Street glorify the empty lifestyles they depict in an effort to expose how toxically alluring they can be. In Killers, it’s not exciting, and Scorsese is saying that maybe it never should have been. There’s no pleasurable excesses, no moments that ride the high of their own self-ingested toxins– just the blatant, excruciating, systemic violence of white male bigotry against indigenous people, sustained by mass quiet complicity and the lies of men who claim to love the people they’re consciously poisoning.

In the end, Scorsese even implicates himself for telling a story that is not his, for pulling from Western mythos based on the revisionist denial of barbaric, racist genocide, and that even through his aching quest for authenticity he’s still complicit in that, still incapable of delivering this story through anything but the perspective of the complicit, the villains who kill en masse for oil, the racists, the lying husband who thinks he loves the Osage people despite his poisoning of them. In what might be one of his last films, he states that telling these monstrous stories is his legacy, but concludes that the stories themselves, and the erasure and downplaying thereof, are the legacy of the American project as a whole. “There was no mention of the murders.”

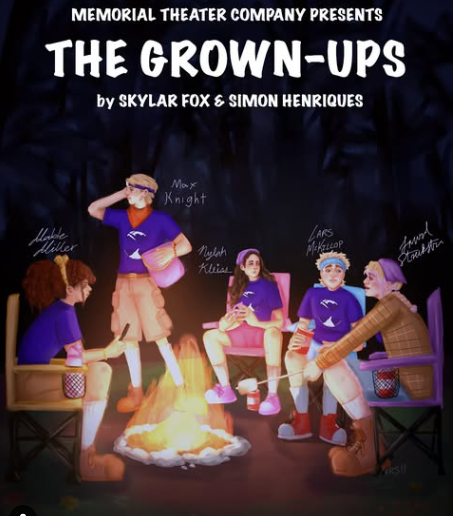

![Image credit to [puamelia]](https://memorialswordandshield.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/3435027358_ef87531f0b_o-1200x803.jpg)