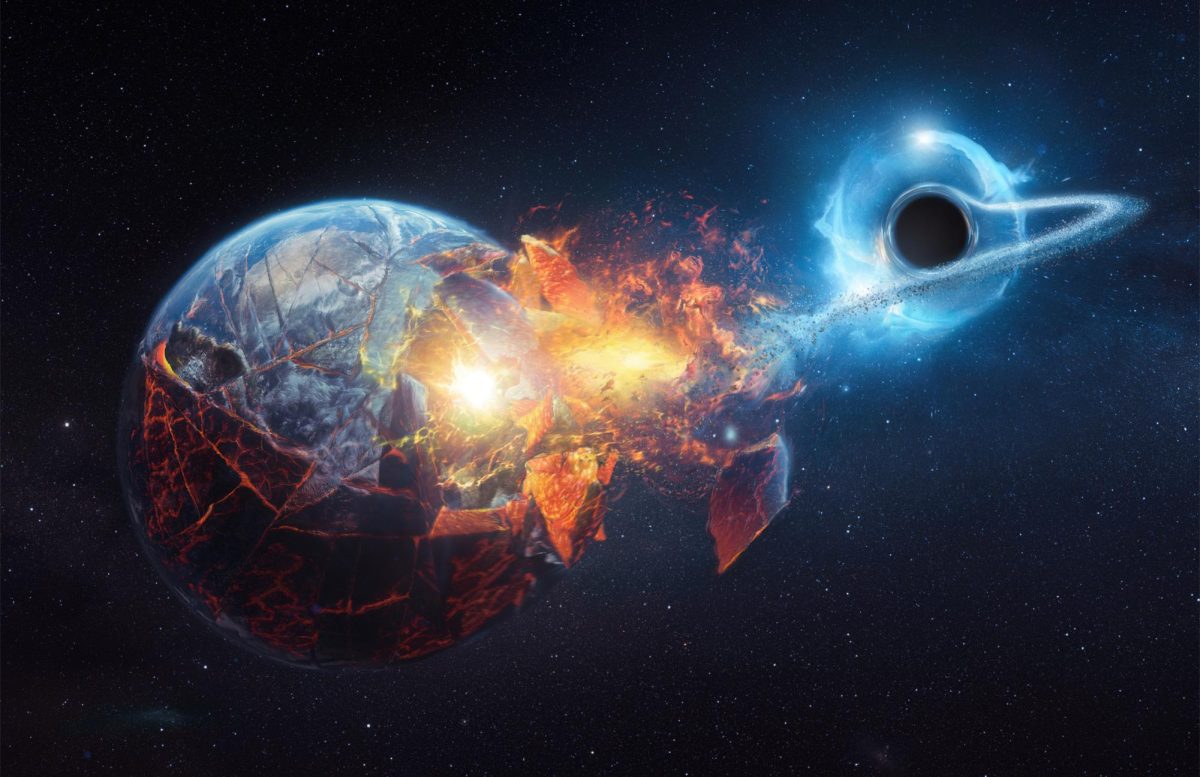

Artificial intelligence has raptured the minds of sci-fi readers and writers for over a century, being used by artists to explore questions about the human condition and our relationship with technology. Over the past decade, real life artificial intelligence has been developing in ways that seem as though our science fiction is soon to become a reality. However, with the rapid advancement of this technology, something has occurred we maybe didn’t expect: there’s a chance that soon, AI might be creating that fiction for us.

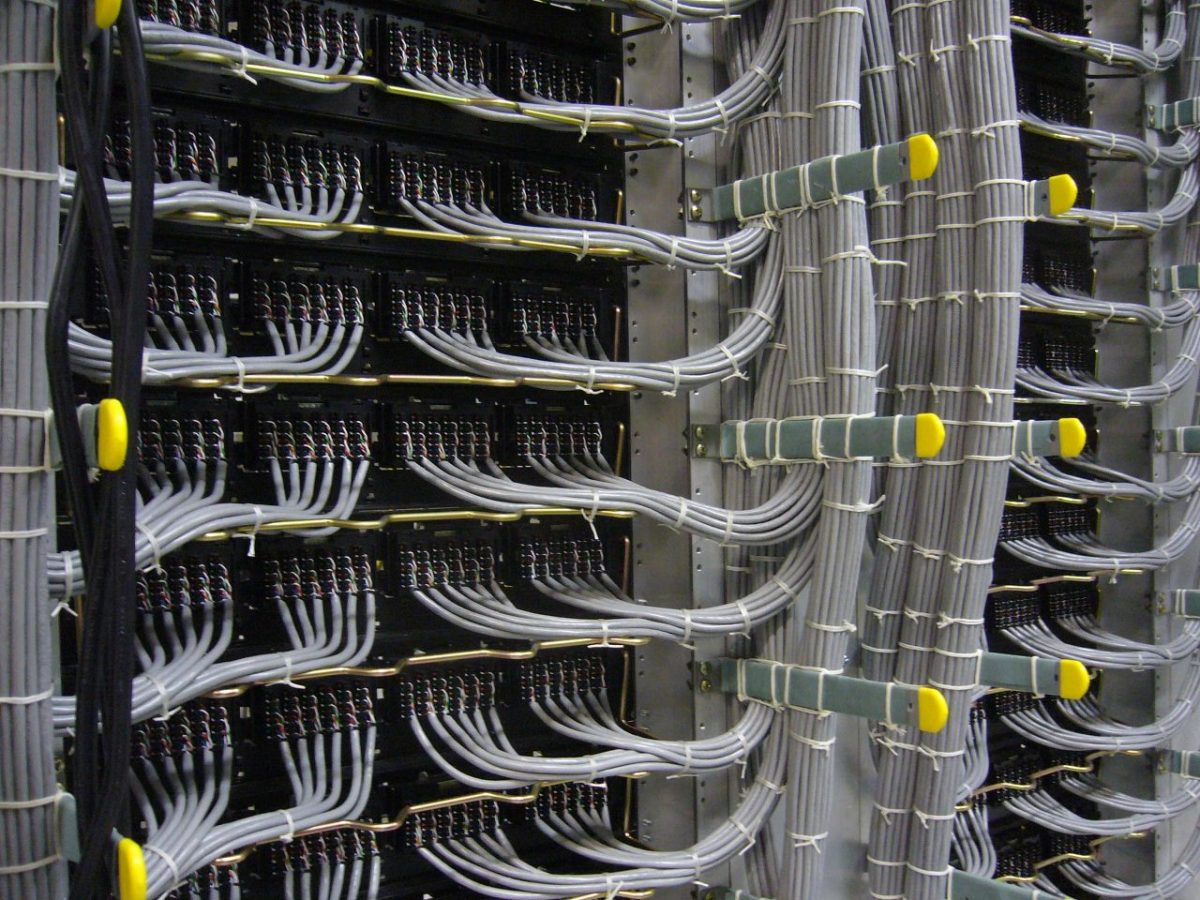

What I’m talking about is the recent boom of application of artificial intelligence to art. Not just the science fiction literature I opened by talking about, though you can generate plenty of that on websites like ChatGPT— AI has been spreading rapidly to all artistic mediums, such as music, photography, and videography. In each of these mediums, the basic principle of AI generation is similar: a prompt is given to the program, which then analyzes patterns in the reference data related to the prompt (whether that be other songs, footage, photographs, etc.) and uses that to algorithmically predict what the prompt could look/sound like based on the training data. The ability of AI to replicate works in these mediums has been improving at an exponential rate. In the past year alone, the idea of AI generated “art” has gone from a burgeoning, curious prospect to what feels like a commonplace practice. Nowadays, there’s numerous sites dedicated to creating whatever you can fit into a short prompt. Need to generate a Sci-Fi short story about cyborg ducks taking over the world? ChatGPT has you covered. Want to have access to realistic images of former President George Bush boxing a platypus in the coliseum while wearing pink leotards? You’re one sentence on Midjourney away. Need a jazzy soundtrack for a short film about noirish talking vegetable detectives? Meta’s new Open source Audiocraft code, or any of the 4 suggested by this recently published Forbes article, can do that for you, if you’re in a particular situation where you need that, I guess. Though AI was once used to represent grandiose ideas about the human condition, its current usage in art is as common and simple as typing in a prompt.

Obviously, I’m making it out to be more trivial than it actually is. Truthfully, the ease that AI generated “art” provides has already led to an enormous growth in the mainstream presence of AI generated content. In the film and TV industry, AI is already making its presence known. Notably, the opening title sequence of Marvel’s recent Secret Invasion show was AI generated, a milestone in mainstream TV usage of the technology. In addition, Netflix and Disney have recently posted numerous AI related jobs, including one listed as “AI Product Manager” that reportedly pays up to $900,000 a year. In the music industry, AI generated music has spread to the mainstream similarly quickly, with DJ and music producer David Guetta recently dropping an unreleased AI generated EDM track accompanied by an uncannily realistic AI Eminem verse during a live show. In conversation with BBC afterwards, Guetta said “I’m sure the future of music is in AI. For sure. There’s no doubt.” Similar technology has been used to create AI generated Drake songs on the music generating site Drayk.it, as well as artificial intelligence generations of fake songs by Ariana Grande and The Weeknd. Even simple AI images made on Midjourney are starting to garner mainstream attraction, with an image called Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial, becoming the first award winning AI generated image last year when it won the top prize in the “digital arts/digitally manipulated photography” category at the Colorado State Fair. AI isn’t just an interesting new toy for people to play around with— it’s something that’s actively inserting itself into and impacting the entertainment industry as we know it.

With that undeniable fact said, we’re left with one question: is greater AI involvement for the better?

Here’s where I have to step in with my own opinion and recognize my bias: I would not be here writing this article if I believed it was for the better. I believe there’s many ethical concerns to something created by an algorithm that “creates” by amalgamating together a collection of other artists’ works, and even more, I find it hard to believe that AI “art” really is art. I believe art is about intention, about the human idiosyncrasies and vulnerability that come in the process of creating something. By handing that process entirely over to a computer, I think something fundamental to “art” is lost.

I’m not the only one who thinks that way. AI’s growing presence in the entertainment industry has already sparked controversy. So far, the consensus among most artists seems strongly against it.

In the film and TV industry, the recent WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike is the obvious example of this. Amongst calls for higher pay and more economic sustainability in an ever changing world of streaming, one of the main demands of the writers and actors is for regulation on AI in the creative process. Writers fear that the ease AI could provide in the writing room could be used to replace or steal the works of real human writers. Kelly Wheeler, a TV writer and WGA member, put into words her own creative anxieties around artificial intelligence in this article by Variety: “I love writing and I love being around writers… And the idea that that creative energy can just be stripped away from television, and instead have a robot do our job – or attempt to – is terrifying.” John Rogers, another screenwriter and member of the WGA’s AI working group, agrees in his own statement in the article: “Should you be worried? Absolutely,” he said. “They’re going to try to use AI to replace writers. Will the shows be good? No. Will that stop them? No.” These fears have already proven to be not unfounded. Remember back to the AI generated title sequence of Secret Invasion and those new AI-based jobs at Netflix and Disney? Well, both were released in the middle of the ongoing strike. Though neither of these display AI influence in the writers’ room itself, the timing of their release in the midst of the strike reads as tone-deaf at best and downright threatening to writers’ livelihoods at worst. In addition, throughout the strike Disney CEO Bob Iger has continued with his insistence on the company embracing AI, which pairs frighteningly with other comments by Iger completely dismissing the demands of the writers during the strike. In response to the AI job postings, actor Bryan Cranston (Breaking Bad, Malcolm in the Middle), had this to say: “We’ve got a message for Mr. Iger: I know, sir, that you look through things through a different lens. We don’t expect you to understand who we are. But we ask you to hear us, and beyond that to listen to us when we tell you we will not be having our jobs taken away and given to robots.”

While the music industry has had no backlash on the level of the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike, there’s still plenty of conversation around the usage of AI in music creation, mostly around the legality of the practice. As far back as a year ago, the Recording Industry Association of America was raising questions about whether music generative sites run by AI infringe on artists’ rights, saying: “To the extent these services, or their partners, are training their AI models using our members’ music, that use is unauthorized and infringes our members’ rights by making unauthorized copies of our members works.” AI replications of major artists like Drake, Ariana Grande, and Billie Eilesh have received similar backlash from people questioning the legality of using the tracks and vocals of those big name artists in their generative algorithms.

However, despite all that, an argument can be made for the usage of AI tools in the creation of art. For one, some argue that the accessibility of the technology allows for a greater democratization of artistic creation, an idea that is not totally without merit. Burgeoning musicians may not have the budget to produce their music at the highest quality, and may turn to AI generation as a sample to pull from. Young filmmakers who might not be able to reshoot for time or monetary reasons can utilize AI to touch up shots or smooth over clunky edits. Even some artists participating in the WGA SAG-AFTRA strike recognize the possible value of AI. John August, a member of the negotiating committee for the WGA, had this to say about the topic: “There certainly is no putting the genie back in the bottle… It’s going to be here, and we need to be thinking about how to use it in ways that advance art and don’t limit us.”

In addition, AI is a very powerful for restoration. Artificial intelligence’s ability to generate sound and image based off of a collection of other input data makes it an ideal tool for touching up old or messed up recordings, whether that be music or footage. One such example could be found earlier this summer, when Sir Paul McCartney announced that he would be releasing a final Beatles song utilizing AI to touch up a shoddy recording of an old unreleased track. Though there is certainly an ethical discussion to be had over the use of AI to modify a dead person’s voice, the fact that AI makes restoration of this level technologically possible is worth recognizing on its own.

Going forward, it seems safe to say that the growing presence of AI in the entertainment industry is unavoidable. Questions of banning it outright are unrealistic more than anything. In the end, I don’t think AI can be discounted entirely, but I do believe it needs heavy regulations, ones that ensure it stays as an aid to the creation of art rather than as a replacement for it. Perhaps AI is a great new tool for creating art, but like any other great tool, it’s still best used in the hands of an artist.

![Image credit to [puamelia]](https://memorialswordandshield.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/3435027358_ef87531f0b_o-1200x803.jpg)