Belgium’s Chocolate Hands Controversy

Controversy over the symbolism associated with the severed hand-shaped chocolates in relevance to Belgium’s history of colonialism in the Congo

October 9, 2022

Full of chocolate shops around every corner of the town, the Belgian city of Antwerp marvels tourists with its wide variety of chocolates. Surprisingly, one of Antwerp’s most popular chocolates is the shape of a severed hand. Legend has it that there was once a Belgian giant called Druon Antigoon who reigned terror on the city centuries ago and a young warrior named Silvius Brabo triumphed over Antrigon by chopping off the giant’s hand and throwing it into a river. Inspired by this folklore, an Antwerpen chocolate company began making hand-shaped chocolates to celebrate Brabo’s heroics in 1934. To this day, the severed hand is the symbol of Antwerp. But the tale of Brabo has largely overshadowed a dark aspect of the Antwerp chocolate hands story. As new light sheds on the history of Belgium, these severed chocolate hands are taking on a completely different meaning.

Several European powers during the 1800s entered a new wave of colonialism centered on Africa. Among these rulers was King Leopold II of Belgium, who seized the Congo in 1885. Yet, rather than controlling Congo as a colony like other European powers, Leopold owned the region as a private property to build a source of wealth from rubber and ivory. By forcing the people of Congo into enslaved labor, he accumulated his wealth through the extraction of Congo’s precious resources. Between 1885 and 1905, 10 million Congolese were murdered by the Belgian king, while countless others also suffered from malnutrition, disease, and torture. The unimaginable violence laid upon the people of Congo in the pursuit of vast wealth is why Leopold’s reign over the Congo is notorious for its brutality.

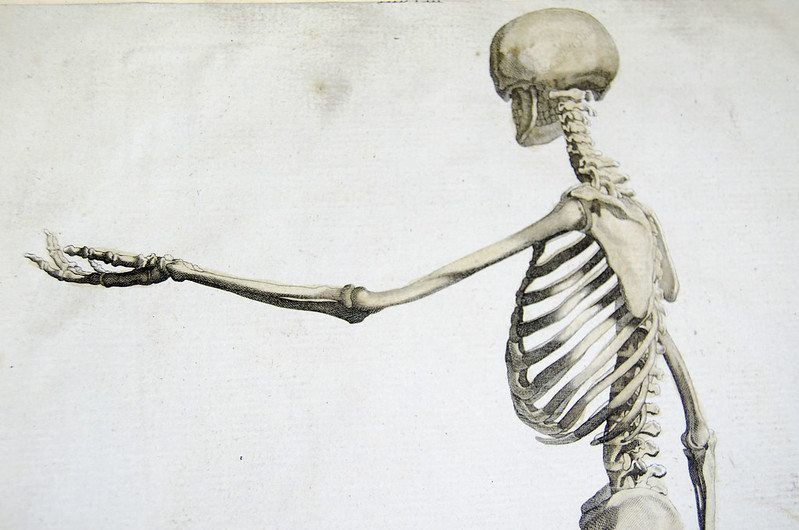

And this is where the controversial hands come into play. When the enslaved people of Congo failed to meet quotas for rubber and ivory, Belgian soldiers would hack their hands as evidence to officials that these slaves were punished. To account for every bullet used when a slave was killed, soldiers were also required to sever one of the victim’s hands to prove that bullets were not “wasted” for activities like private hunting but for an “approved” purpose. As the number of murdered victims rose dramatically, so did the pile of hands.

Word of the Belgium Empire’s atrocities soon circulated around the world through articles, pamphlets, and books written by some of the most prominent writers like Mark Twain and Arthur Conan Doyle to draw more attention to Belgium’s human right abuses. Eventually, Leopold was forced to hand his colony over to the Belgian government, and with it, the hand-chopping practice also came to an end.

While the debate rages over whether Antwerp hands should be banned due to a convoluted story of symbolism, there are two crucial points that must be considered in this chocolate controversy. One is that symbolism matters because the Antwerp hands symbolize a violent chapter in Belgian history. Regardless of Antwerp’s true intentions for creating Antwerp hands, to insist on making them is to mock the countless Congolese who were tortured and murdered under Leopold II. Another point is that the Antwerp hands simply cannot be a coincidence. Even though the origin of Antwerp hands is still under speculation, it is virtually impossible that when Jos Hakker came up with the idea of chocolate hands in 1934, he had never seen any circulating picture, article, or book depicting the hand-chopping practice beforehand. Had the people of Antwerp, including Hakker, really forgotten about the crimes committed against the Congo when they chose the severed hand as the city’s symbol?

The last key thought to take away from this is about Leopold II’s rather untainted legacy. Despite his infamous brutality on the people of Congo, rarely has his legacy been criticized with the same fervor as that against Adolf Hitler, for example, largely because of the World Wars that immediately followed Leopold II’s surrendering of his colony. As the world was occupied with criticizing Hitler’s role in WWII, Leopold II’s legacy slowly made its way into Belgian history textbooks, embellished to cover up a rather uncomfortable history of colonialism. But it is your job, as the reader, to retrace the footsteps of the past and preserve historical truth, even if it involves the darkest chapters of history. While banning the hand symbol is certainly a crucial measure to rewriting the distorted narrative of colonialism, teaching those around us about this uncomfortable topic is ultimately our primary responsibility to provide our next generation with a more concrete understanding of the problems they may face in their time.